Cat Goodrich

Faith Presbyterian Church

Baltimore, MD

July 17, 2022

Faith Values: Social Justice

Amos 5:12-15, 18-24, Mark 12:13-17

The email came out of the blue one morning, from my husband, Dary: Did I know an immigration lawyer in Atlanta? His colleague Julia’s friend had been detained, and needed representation. Flipping through my mental rolodex, I realized that though I didn’t know anyone who did immigration law in Atlanta, I did know an attorney in Birmingham who might, so I made the connection. Thus began many months of work and waiting, as the young man’s case wound its way through the immigration system, as it existed under the previous administration. He was held with countless other men in a detention facility outside of Atlanta. while his wife, who was pregnant, was released on her own recognizance to stay with an aunt in New York.

He was still detained when his daughter was born, hearing the news of her birth on a payphone, the line scratchy, handset cradled against his shoulder as he stood in a florescent lit hallway, surrounded by other detainees. Like so many other migrants from Central America, he was seeking refugee status, awaiting the trial that would determine his fate. It was a trial he was likely to lose, despite having fled Honduras in fear for his life after a gang threatened his family should he refuse to pay for their protection.

My lawyer friend would update me from time to time about the case – but I admit, the heartwrenching suffering of detention and family separation were not at the forefront of my mind as I went about my daily life in ministry, or day-to-day with my family. We compartmentalize to get by, we have to. Otherwise, we become paralyzed, overcome by the enormity of the disasters unfolding all around us.

I did not know Jose, the man who was detained. I’d spoken to his wife Catalina only once, to introduce her to the lawyer – but still, however tenuously, our lives were connected. As a taxpaying citizen of these United States, I was complicit in his detention, complicit in upholding the system that determined he was at risk of failing to appear for court proceedings if he were released, and so locked him away in rural Georgia for more than a year, eventually deporting him to El Salvador.

And so it is that this story from the gospel of Mark and the question it poses, from so many centuries ago, comes alive for us today. Jesus, teaching in the temple, is approached by an unlikely alliance of religious and civic leaders – who ask: Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not? They’re really asking: Is it faithful? To whom do we pledge our allegiance? To Caesar, or to God? And it’s not a fair question, because there’s no right answer, no safe answer. Not in Israel, an occupied land, held in the tight fist of Roman rule for almost 100 years at that point.

The tax in question was a head tax, one everybody had to pay – it covered the cost of the occupation. Nobody wanted to pay it, the community resented it, and of that there is no doubt. But the question posed to Jesus is a double-edged sword. See, many Zealots who resisted Roman rule refused to pay it. If Jesus says, “pay the tax,” he will anger his supporters; if he says, “refuse to pay,” he risks outing himself as a revolutionary, giving his opponents reason to report him to the authorities and therefore risking arrest, and crucifixion.

It’s a trick question, meant to trap Jesus into saying the wrong thing, but it’s also a question worth asking ourselves even today. Now, don’t get me wrong: I pay taxes. I believe in public schools and fire departments, garbage collection, and well-maintained roads, critical infrastructure and public safety, international diplomacy, and any number of other crucial services provided by our government. But as people of faith, we owe our ultimate allegiance not to the state or our country but to God. And our taxes pay for all sorts of other things, not just the glue that holds our government together but also bombs and bailouts, drones and detention centers. This should give us pause, and why it’s worthwhile to consider this tricky exchange between the Pharisees and Jesus. Why I’m grateful for his strategic response. How do we faithfully navigate conflicting demands for our time, talents, and resources? To whom do we pledge our allegiance?

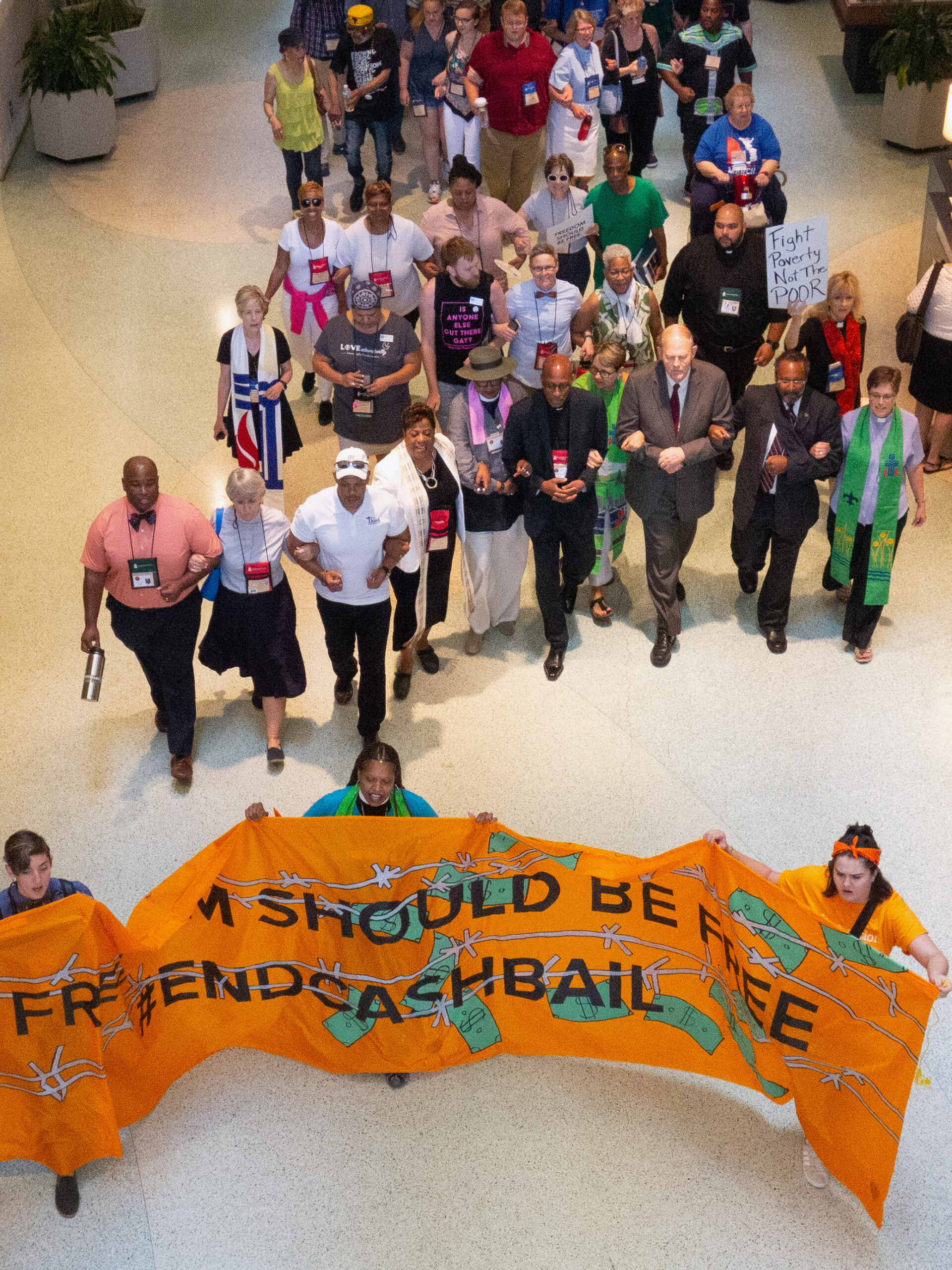

This Sunday we are considering the Faith Value of Justice – a big umbrella that covers social, racial, economic, environmental, gender and LGBTQ justice, all causes dear to our heart as a congregation. What is justice? If we believe Cornell West, justice is what love looks like in public. Richard Rohr describes justice and compassion ministries as the movement of the holy spirit within us for the sake of others. He talks about three ways faithful communities respond to the needs around us by telling the story of a river that overflows its banks. You may have heard this described in other ways – ambulances on a mountain highway, or pulling babies out of a river. Rohr says, one way our ministries respond with love to the needs right in front of us is through charity. We pull the people out of the water when the river floods, help them get to dry land, provide clothes, food, and shelter. Another way we respond is through ministries of education and healing: training people to be lifeguards, paramedics, doctors and nurses, better equipped to respond when the river overruns its banks, teaching skills and helping them to make a life for themselves out of the floodplain completely. But justice looks upstream, and says – why is this river flooding in the first place? The work of justice then advocates and builds power through campaigns and coalitions to strengthen the levees, or build a dam, and hold the engineers and politicians accountable for keeping their people safe. All of these are necessary for thriving and healthy communities.

We can’t do everything, but we can do some things. It’s why some of us are called to serve as deacons, serving and caring for our community with compassion by providing meals and groceries for the guys at Harford House; visiting our sick and homebound members; praying for our congregation; supporting the CARES pantry; and building affordable housing through Habitat. And others are called to serve on the SEJC, our social and environmental justice council, inviting our congregation to advocate for an assault weapons ban, electric vehicles for the USPS, full staffing and better service on the mobility bus for elderly and vulnerable people in our city, and an independent immigration court in Maryland to name a few issues we’ve acted on this year.

We do this work out of our conviction that God needs our hearts and our hands, our bodies and resources to share mercy, build peace, and pursue justice in the world. And it’s a world that is organized by systems of government which we must navigate as faithfully as we can. While Jesus’s response to the question about paying taxes was a bit oblique, give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s, his ministry and teaching is clear: he heals the sick, serves the poor, and feeds the hungry. He challenges the rule that oppresses his people and the boundaries that shut people out. He enacts God’s grace and liberation, and heralds the arrival of God’s reign.

The coin that Jesus asks for was a denarius, which had a picture of the emperor Tiberius and the phrase, “son of the Divine Augustus.” It was a graven image, and a claim of divinity – two things forbidden by the 10 commandments. Ostensibly, the coin belongs to Caesar. But doesn’t all of creation belong to God? Are we humans not reflections of the divine image? How can we give to Caesar what is Caesar’s when everything belongs to God? And so it is that the wise teacher calls us to strategic nonviolent resistance of affirming God’s image in every person that we meet. Because when we see that, we cannot tolerate their suffering. We must devote ourselves to their flourishing, putting ourselves on the line for the sake of the world that is becoming.

We cannot do everything. But we must do something. I don’t know what it is for you. Who it is for you. What issue breaks open your heart and keeps you up at night, what you’ve written about to your legislators and to the President and talked about with those who will listen. Maybe you don’t know what it is yet. But we are called into communities of care and accountability so that together we can testify to the truth that God’s will for us is to be whole, to be loved, to flourish. And calls us to work together until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. May it be so.