Cat Goodrich

Faith Presbyterian Church, Baltimore, MD

March 7, 2021

Turning the Tables

John 2:13-25

Kelly Ingram Park covers two square city blocks in downtown Birmingham. The park is crisscrossed with paved walkways, and there are various statues and fountains shaded by sprawling live oak trees. It’s a pretty quiet place, without much foot traffic most days. But when George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police in late May of last year, the community gathered there in Kelly Ingram to share our pain and anger. Not because the park is the most centrally located, but because that’s where 16th Street Baptist Church stands, where the 4 girls were killed in 1963 by a white supremacist bomb. And that’s the place where, 57 years ago, Birmingham police used firehoses and dogs to terrorize children who dared stand up for their civil rights. There is history there: history of courage, tenacity. The memory of collective outrage hangs thick in the humid air.

That protest was the first time since the start of the pandemic that I had been around crowds of people, still awkward in my mask. But it felt important to go, to stand with others, to bear witness together, to call for accountability and a change in the way policing happens in our country. Lots of people spoke, young and old, faith leaders and activists, including T Marie who led our Adult Forum this fall. One who stood out was a guy named Jermaine Johnson, a local comedian who calls himself Funnymaine. He drew the crowd’s attention to the Confederate monument in front of the courthouse, in the next park over, Linn Park. The previous mayor had covered it with plywood and was fined by the state for doing so, but it still stood, a sandstone obelisk 52 feet high, a stark reminder of the city’s racist history. “There are some things I can’t say here,” Funnymaine told the crowd that day. “I can’t tell you to go over to Linn Park after this rally… I can’t say that’s where I’ll be. We’ve got to protect our city. But it would be a shame for that monument to be torn down. But I can’t tell you that,” he said.

The march that afternoon was peaceful. People from all walks of life, every age and stage stood together in the shade. But later that night at the monument a different crowd gathered, with chains and trucks and sledgehammers and spraypaint, determined to tear the obelisk down. The Mayor went and asked them to stop before someone got hurt, let the city remove it safely. Give me 48 hours, he said, and it will be gone. The crowd backed off and disbursed, but some were still seething with anger. So they ran through downtown, smashing windows, wreaking havoc.

You here in Baltimore are not strangers to that kind of anger, anger that smolders until a match gets lit and it turns into a conflagration. Anger that destroys. We don’t condone it, but we can understand it. After all, there is a lot to be angry about these days. So much.

Look around, talk to folks about what they’re struggling with, and you’ll find something to be mad about. Calibrate your news and newsfeed correctly and you can be fed a steady diet of bitterness, endless fuel for fury. I have tasted more anger than I want to admit since the world shut down a year ago. Macro anger at federal government mismanagement and denial that worsened the crisis of the pandemic. Anger at callous disregard for human life, at the racist systems that bind us. But I’ve also felt micro anger: ordinary, everyday, run of the mill mad – My temper flaring at tiny infractions, the stress of parenting in a pandemic. And I’ve become more familiar with the anger of my children. I try so hard to do as I coach them, to breathe, to step away, to be mindful and kind. But – it’s hard.

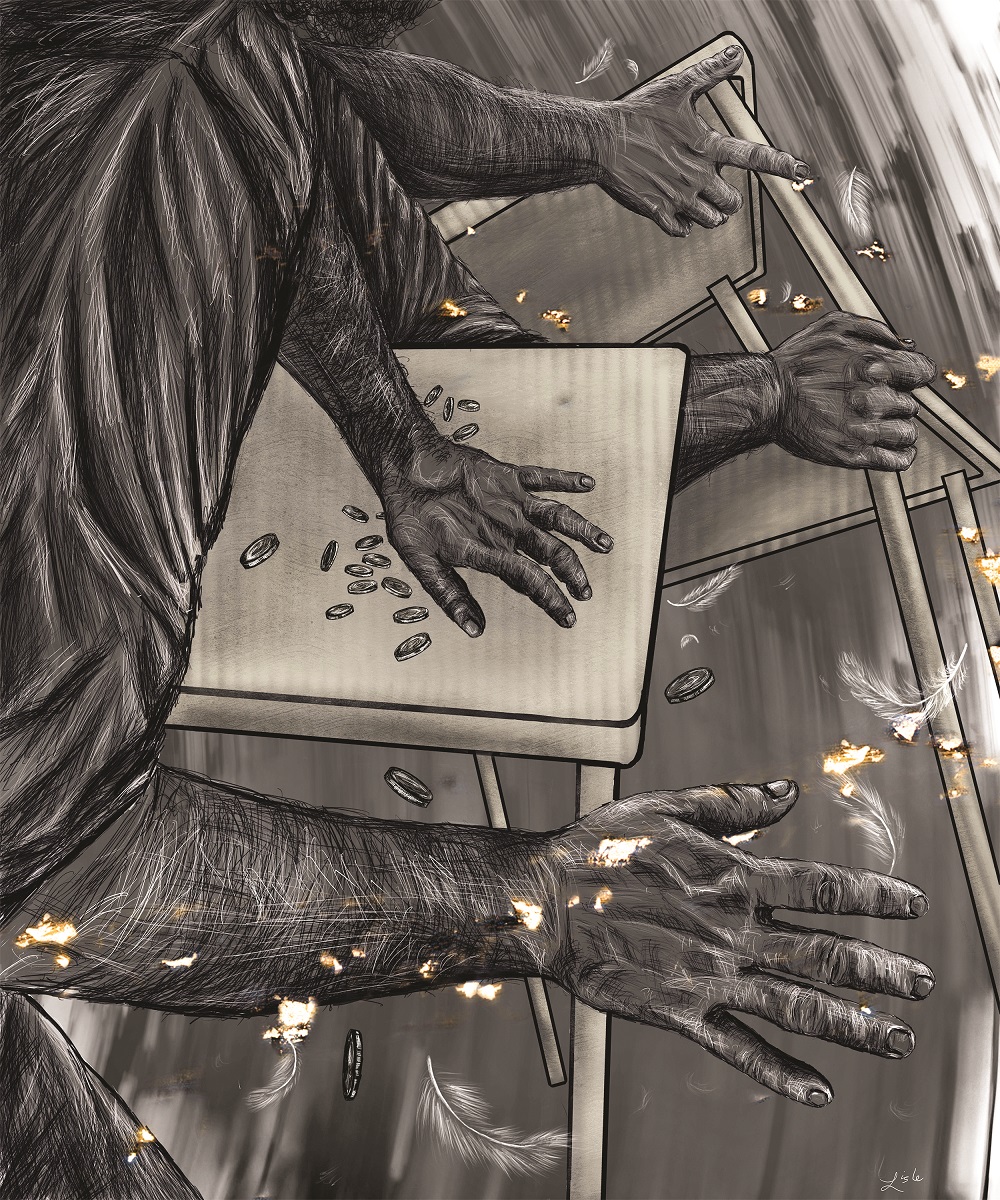

Does it help to know that Jesus got angry, too? That he turned over tables, threw people out of the temple, pilgrims and merchants, driving them and their animals out with a whip? In his fury, he disrupts preparations for the biggest festival of the year, the Passover, which would have been a huge source of income for the temple and the market.

I don’t know about you, but I take some comfort in this story. God gets angry. Christ came, in part, to experience the fullness of life, to be human – to feel all the joy and the grief, the fun and the struggle, the love and the suffering. Through Christ, God feels the height and depth and breadth of the human experience. Whatever we’re going through, God gets it.

This incident, this stunt in the temple is recorded in all four gospels, which means we’re pretty sure it happened. And it’s a story that humanizes the miraculous healer and teacher – adds the depth of righteous indignation to our picture of Jesus. What was he so angry about?

Different versions of the story emphasize different sources, different reasons for his anger. The house of God co-opted by the forces of the market. A system of worship that needlessly involved animal sacrifice. People with power making money by taking advantage of people who were in need.

See, here’s what was going on: people travelled to Jerusalem to worship for Passover. Worship involved sacrificing an unblemished animal – which pretty much meant the animal had to be bought on arrival. Out of towners had to change money to the temple currency — at an unfavorable rate — then buy an animal to sacrifice — at an inflated price. It’s like buying a meal from Doordash or some other delivery service: you don’t have much choice in the matter so they can charge you and the restaurant whatever fees they want. Jesus was angry because the temple moneylenders and merchants were trying to make a buck off the people who came to worship. By disrupting the lending and driving out the animals, Jesus throws the whole system into chaos. He challenges the temple’s corruption, and by proxy, Rome. Rome appointed the chief priest after all, and received a portion of the tithes people offered there.

But that’s not all that’s going on here. The gospel writer, John, wants to expand people’s thinking about where God could be found. In ancient Israel, God’s presence among the people was located first in the ark of the covenant, then the tabernacle, then the temple in Jerusalem. But in the year 70, the temple was destroyed. Without the temple, how would people worship and encounter God? That’s what John is trying to answer. In these verses, we hear Jesus foreshadowing his death and resurrection. But he also calls himself the temple: “Destroy this temple, he says, and in three days I will raise it up.” God’s presence is made real in the world in him. In Christ, God is not hidden from the people in a secret sanctuary. God is out with the people, let loose in the world, and angry about injustice- turning over tables in the marketplace and driving out the livestock and the lenders.

Some interpreters think Jesus planned this event. They believe he didn’t lose his temper, but instead pulled the stunt strategically, to provoke and disrupt a system of oppression. Think about it: he turned the market into chaos to challenge the temple leaders and the Roman authorities during the busiest time of the year, the Passover, to disrupt their system of profiting off the poor.

There is a lot to be angry about these days.

We don’t have to look hard. Vaccine distribution that leaves some behind, especially poor communities of color. Lines of people out of work, waiting for boxes of food. Students who still don’t have reliable internet and are falling farther behind their peers. Hundreds of children still separated from their families by our government. States ending mandatory mask ordinances and reopening restaurants with no capacity restrictions – decisions that will be deadly for far too many.

The father of community organizing, Saul Alinsky, said good organizers find the wounds of the people and rub salt in them – anger motivates. Anger gets us out in the street, crying out for justice, organizing for change.

That’s what Jermaine “Funnymaine” Johnson was doing. Less than 24 hours after the Black Lives Matter rally, Mayor Randall Woodfin had a crane and a truck remove the monument, risking a fine of $25,000 from the state. But you know what? The guys who actually did the work didn’t charge the city anything for their time. And a group called white clergy for Black Lives Matter raised more than $60,000 in a day to help the city pay the fine and to cover the cost of removal.[1]

Across the country, nearly 100 Confederate monuments were removed in 2020, more than the previous four years combined. That change is the result of the public outcry and sustained anger at police brutality and racism, and the recovery of historical memory around when and why those monuments were erected in the first place. In some ways, it’s easier to take down a monument than it is to transform the entrenched culture and structural racism of our criminal justice system. But it’s a step forward in the larger and longer journey toward our collective liberation, love, and justice. The work continues. And if the past year has taught me anything, it’s that anger, stress, and anxiety are exhausting. They can deplete us. Anger can’t be all we have. And thank God, it isn’t. That’s why God calls us into community, and gives us to each other. We have this place. We have each other. We have faith in the one who Rome could crucify but could not kill, whose example inspires, whose performance art provokes, who brings us into relationship with the living God. Relationship which sustains, and transforms, and continues to move us forward toward the promised land. Thanks be to God.

[1] https://www.gofundme.com/f/take-down-birmingham039s-confederate-monument?fbclid=IwAR0QqoKHSj5xexnYoyAEnlWNoMLJ8pP6BqKXxFrNSBMmt2xXE67Bl0BLAhs